It seems to me that the value of data is in how it’s used. At MIND Research Institute, we use data to drive decisions on a daily basis. Internally, we monitor student success data and make program adjustments in response to that data.

But this is not the information that most teachers care about day to day in their classrooms. Nor is it what keeps over 1.2 million students so engaged with ST Math that they log in 365 days a year—even on major holidays!

Our product team is focused on what teachers do care about and on what motivates kids and helps them learn. We are currently deep in a redesign of ST Math®. Our neuroscientific method that engages students’ perception-action cycle and teaches conceptually before procedurally is staying the same. We have the data to prove our program works. However, we know we have opportunities to improve how we present student success metrics.

Over the past two years, we’ve spent over 826 user experience research hours interviewing, observing, and conducting usability studies with over 935 teachers, administrators, and thousands of students.

We have also conducted numerous interviews and usability studies with our internal teams. Our colleagues witness first-hand the impactful work being done in our schools, but also see the occasional errors of good intentions.

Following each research study, our design team iterates and makes improvements on our prototypes based on the findings from the field.

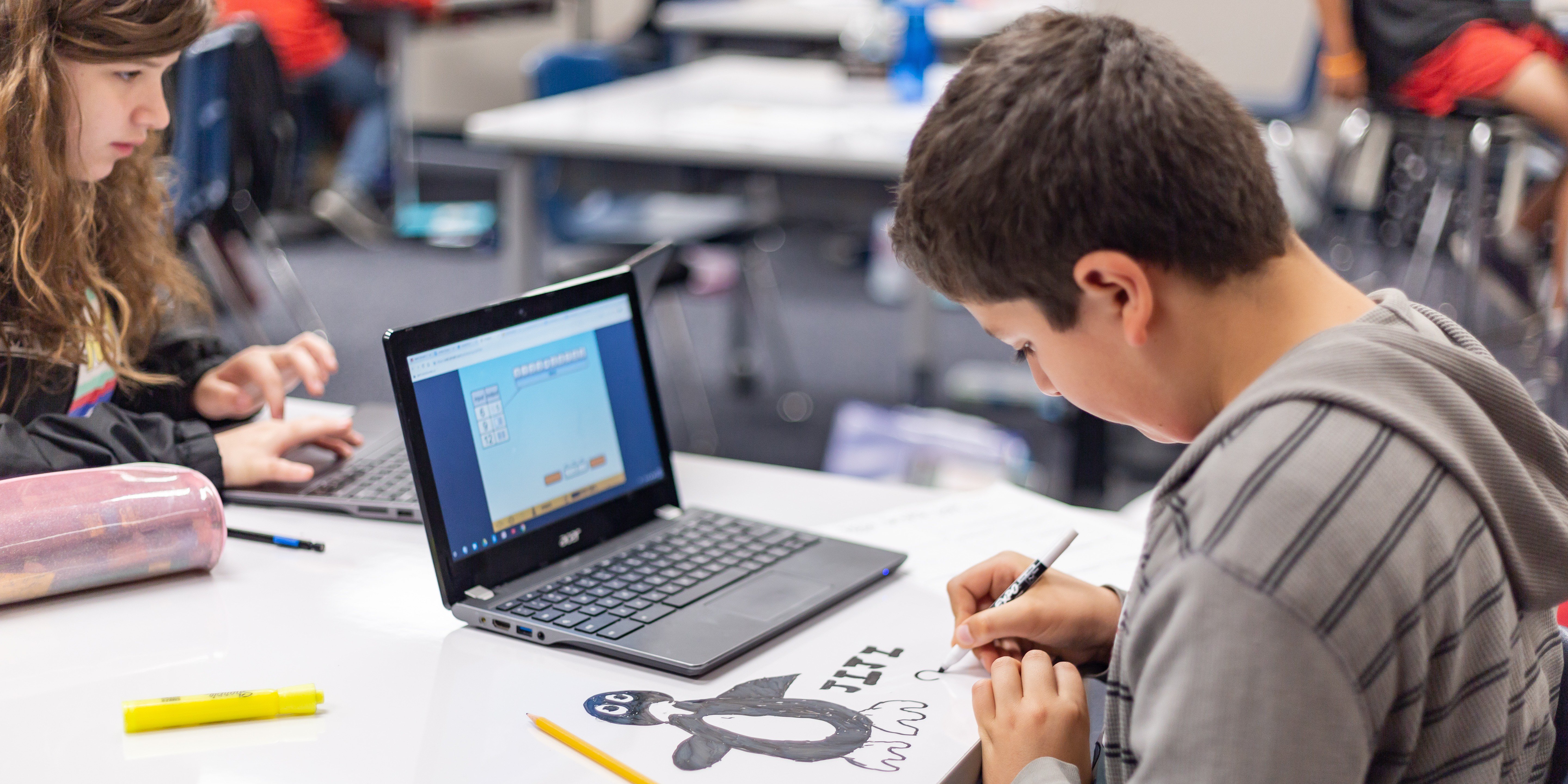

Through these studies, we’ve met educators who are maximizing the power of ST Math by supporting students’ innate abilities to learn by doing through trial and error.

We’ve learned how teachers across the country are bringing ST Math puzzles into their core curriculum to kick off new units or to approach a concept in another way. We’ve watched students share strategies and learn from one another during Puzzle Talks. We’ve met “JiJi champions” and witnessed excitement for math and celebrations of JiJi joy.

But we’ve also witnessed some struggles that are unproductive. We’ve seen good but misaligned intentions defeat the proven methodology and lessen the effectiveness of ST Math.

Here is where we see that the value of data is earned through the actions it enables.

Presently, students’ success in ST Math is tracked primarily by their percent progress through the program. Of course ST Math provides many other metrics of success, but what our studies found is that teachers do not have time to dive into these additional metrics with much regularity.

We learned that when teachers focus in isolation on percent progress, some help their students complete puzzles without giving them sufficient time to engage with, think through, and act upon informative feedback. We witnessed teachers, parent helpers, classroom aides, computer lab techs, principals, and peers helping students by showing them how to complete ST Math puzzles.

By short-cutting the academic rigor ST Math is so well known for, this sort of help can contribute to decreased student engagement and even an aversion to math! Students should have to figure out how to think about the problems the puzzles pose.

While it may be well-intentioned, the information these “helpers” are missing is that students learn best through engaging their perception-action cycle. When a classmate who has already solved a puzzle leans over and tells a peer how they did it, that bypasses that student’s opportunity to take action in response to the informative feedback of their attempt.

When a student is encouraged to raise their hand for help from their teacher after just three to four attempts, that student learns to rely on the teacher rather than develop problem solving skills.

Picture a baby first learning to walk. Now, imagine after a third fall on their diapered bum, the parent stands the baby up, supports them around the middle, and moves the baby’s feet right, left, right, left. That baby might learn to move their feet but they won’t learn to balance, use their core to stabilize themselves, or how to avoid obstacles.

The same thing happens for students who are not given the time and tools to properly problem solve in ST Math. They miss the underlying math concept in a format that introduces them to visual representations. Without understanding these underlying concepts, they’ll have a harder time later on when they begin to tackle more challenging puzzles and math subjects.

This is not to say students should struggle through challenging puzzles unsupported. We also witnessed students who got stuck on particular puzzles and attempted the same puzzle many times without coming to the attention of a teacher because their teacher was focused on time (minutes per week) as their sole metric.

These examples of too few attempts before receiving facilitation and too many attempts without help were the extremes. We saw enough variation distributed between these two extremes to know that our next generation of ST Math needs the data to be more easily accessible and actionable.

Our product team has been focused on designing, usability testing, and iterating on the necessary granularity of student success metrics and their respective data displays. We knew we were close to a successful design when the teachers in our studies began to recognize their students by their behaviors in our prototypes, even with pseudonyms.

Using our prototype, these teachers could quickly come up with facilitation strategies for the students whose data indicated they’d reached a point of unproductive struggle. They could instantly see which students were less productive because they weren’t making use of the full time allotted for ST Math. They were able to recognize their “off task” students, their “perfectionist” students, and their students who might need more encouragement—but not yet full facilitation support.

Teachers are pretty great at knowing what to do to motivate individual students to learn. When data is offered in consumable nuggets, easily understandable metrics, and visually clean ways, teachers are better able to get the most out of the learning tools and methodologies available to them. The right data, displayed in the right combinations, and in the right visual format empowers teachers and supports their impactful work with their students.

Once we reached a high level of confidence in the displays of student data, we began working on how that data rolls up through the class, grade, school, and district levels. And as with any complex design, we’ve had to return to the drawing board multiple times. As much as we want to empower teachers to support their students’ learning, we also want to empower administrators to support teachers’ implementations of ST Math to ensure expected results.

As we launched our redesign in its beta version to our Innovation Team schools this school year, we continue to make sure data is properly actionable and brings about desired adjustments to program implementation and usage to maximize effectiveness. We want to get the highest value out of data so our schools can get their highest value out of ST Math.

We’re grateful to the schools who have welcomed us in to conduct user experience research, and especially grateful to our Innovation Team schools helping us to test each new feature as it is launched into the beta version.

We’re working to identify ST Math partners willing to participate in usability studies focused on assessment data in the coming months.

It’s an exciting challenge to make data easier to understand and act upon. We have our work cut out for us, but we continue to iterate, test, and iterate again on this upcoming new generation of ST Math.

Comment