As MIND Research Institute looks to grow, learn, iterate, and improve in service of our students and educators, we continue to engage in conversations between colleagues and partners. What follows is a discussion between Twana Young, Kayla Mack, and an audience that took place at the 2022 SXSW EDU Conference and Festival. It has been edited for length and clarity. You can listen to their full dialogue here.

Kayla Mack (KM) is an education program specialist at the Ohio Department of Education. She’s worked alongside Twana and her team at MIND Research Institute as a volunteer parent advisor on the Math by Design team. Kayla has been in education for a little over eight years. Before working with the state, she was an assessment coordinator and teacher for a school where she supported students with cognitive and behavioral exceptionalities.

Twana Young (TY) is the vice president of curriculum and instruction at MIND Research Institute. She’s worked for the organization for almost eight years and has worked in education for almost thirty years. Twana was an elementary teacher, middle school math teacher, and school improvement coordinator. Then, she spent a large chunk of time as the director of math science and technology for a large urban school district. Twana has devoted her entire career to making math education better for our students—especially the ones who struggle most, which often are students of color.

TY: Can you describe in one word, what it means to cultivate mathematicians?

Encourage, grow, engage, foster, power—these are some good words. We’re going to dig into cultivating mathematicians. This idea of:

One definition is to foster growth. We’re going to cover three areas of how we foster the growth of mathematicians:

I want to start by telling you a story about a former student of mine named Dante. Dante was an African American boy in my sixth-grade class. On the very first day of school, he walked up to me and said, “Ms. Young, I can't do math. I used to be good at math until fractions. Fractions taught me that I cannot do math.”

The sad part of this story is that way back in third grade, when he was nine years old, Dante thought he had reached the height of his math ability and could go no further. Dante coming to tell me that on our first day together was a way to set my expectations and to let me know that he couldn't do it. He wanted me to know that.

Dante had been spending all those years just surviving math. We have many kids that spend their years surviving math because they feel like somewhere in their past, they peaked and can't go any further. They can't learn anything more because they're not smart enough, and then every failure reinforces what they think about themselves.

KM: I can relate to Dante's story. Early in my education history, when I walked into my math class, I just felt dumb. I felt less than my peers, and it made me feel small in that space. Not having any representation, or way to connect what I was learning to myself, it made me feel like math wasn't a space for me and I developed anxiety. I had this severe math anxiety, and like Dante, I was just surviving year after year.

This mindset carried into my life as a young adult. That anxiety transitioned into avoidance behavior and shame when it came to involving myself in anything that had to do with math. So much so, that it started to penetrate essential parts of my life: general finances and conversations about savings and benefits. When I was in the workforce and having conversations about benefits, instead of embracing opportunities to establish financial wealth, I didn't want to hear anything about it because of that anxiety.

It wasn't until college that I had my “aha” moment and surprisingly, it was in a statistics class. The class elevated my appreciation for math because it made connections to my passions and interests in educational psychology. It came alive for me. I was able to start to understand not just how statistics related to the world around me, but general math. It became understandable, and I began to break the mindset of anxiety and fear in the space of math.

TW: I’m so happy that when you got to statistics, you had an “aha” moment and you saw how beautiful math can be. How it's in everything and it started to make sense. But I’m so sad that it took until college for that opportunity. I just wonder how many people have that same story. We need to do something about that.

When I think about DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion), and I think about the kids that we're trying to reach, it is so much more than earning a grade in school. It is so much more than that because it affects their ability to think about their opportunities, livelihood, ability to build wealth, and understand things.

We've got kids that are not thinking about this, but we need to be thinking about this. How do we get students in a good relationship with math so that they can really start to think about it in a way that makes sense? We must reach that sense making part, and it won’t be by doing more of what we've been doing. What we've been doing isn't really working. It will be by finding a different way.

I want to share this quote by Kofi Annan, former secretary-general of the United Nations.

Knowledge is power. Information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress in every society and in every family.

We tell kids knowledge is power, but I just want to look at that first sentence: Knowledge is passion. Right now, we have kids like Kayla that leave K-12 and don't have that passion, knowledge, or power. We need to empower our students. We must figure out how to do that. That's what set us off on this project that we're going to tell you about today. We know that power comes through knowledge, ability, confidence, and opportunity, and that affects every family. It affects our society. It affects generations.

When you get a parent who comes in during parent/teacher conferences and says, “Well, I’m not good at math either,” that's a generational thing. Parents will say, “No wonder my child’s not good at math, I wasn't good.” We've got to break that cycle because that's where the power is.

I want us to think about how we amplify these things in education. If you're a student like Dante, all that gets amplified to yourself, your teachers, and your parents are your gaps—that you don't meet the standards and that you're falling behind. That deficit-based language just serves to reinforce the fact that you are not a math person—that math is a thing to sort and select, and you got selected in the wrong pile. That's the message that we send when we amplify language like this: there’s something wrong with you.

That is not the case. There’s nothing wrong with the student. There’s something wrong with the system and we must fix it. Instead of saying, “What's wrong with us,” we need to think about what's right with us.

That's where we went on our journey. We know from the research of Jo Boaler and Carol Dweck that the difference between students who succeed and students who don't isn’t about the brain. It's about the approach to life, the learning opportunities they have, and the messages they receive about their potential. We must think about the way that we language things because language informs reality. We must use our language wisely.

KM: I was that kid who sat in the back of the class. I tried to hide behind my peers, hoping that I would never be called to the front of the room to solve a math problem in front of everyone. I had this belief that I would certainly be wrong and as a kid, that is overwhelming. Before I even walked across the threshold of that classroom, I already had this fixed mindset that I was a failure. I couldn't learn because I was so fixated on this idea of being unable.

One of the things that's great about working with Twana and her team on the Math by Design work is that we get to share these narratives. We get to make our implicit ideas and understandings explicit in the development of lessons and materials that are going to help support students in their learning experiences.

TY: I don't know if you ever read this big, long report that came out back in 2008? The National Mathematics Advisory Panel made this report. They were commissioned to study the state of math education in the United States. One of the things that they found is that children's goals and beliefs about their ability to do math directly correlates to their actual ability to do math. Teachers everywhere said, “Of course. We knew that already. We knew that if they don't believe they can do it, they won't do it.” Another finding was that this belief was pervasive in African American and Hispanic boys.

We want kids to have perseverance. We want them to know that failure is just part of the learning cycle. We must help them understand that failure is not an endpoint. It is needed for the whole cycle to work. It will not work unless they fail and learn, and they continue to grow from that.

Part of this is changing the way people think about things: this idea of a special math gene that some people have, and some people don't. That's nonsense because it doesn't exist. The truth of the matter is that math is about thinking, and all kids can think. Therefore, all kids can do math.

That's a message that all our kids need to hear. They can reason, and they can figure it out. They can do it, and they can learn from it. We need to build that up in them. That's what we've been trying to do. That’s our why: the why we're doing this.

And what does DEI have to do with it? At MIND, we have this project that we started and that's the work the Math by Design team is helping us with. Internally, we began by looking at our organization’s mission statement: to ensure that all students are mathematically equipped to solve the world's most challenging problems. Upon reflection, we weren't doing everything we needed to achieve our mission for all students, so we started digging into that.

What does it mean to truly equip all students? It means we must use a DEI lens, and we must change the narrative that there are some people who can do math and others who can't. We must change the way that kids see math so that they see people who look like them doing math. Representation is so important.

We began to look at diversity:

Then, we wanted to look at equity. We needed to bring equity into:

Then, we looked at inclusion:

These are the three lenses that we used when we started pushing on this DEI approach. Here are some examples.

We asked ourselves, “Can we highlight ways that students are already?” So, when you have students like Dante and Kayla, how can we highlight ways that they're already mathematical?

Do you remember making these little fortune catchers when you were a kid? You probably made them in elementary school, right? We have kids that will sit in our class, and they will tell us they can't do math, or they don't understand, but they make these fortune catchers. These fortune catchers are made up of fractions: two parts, four parts, eight parts. This is a great way to say they're already doing math.

Do you have gamers in your class—kids that play video games? If you've ever seen one of those video game maps, it's going to show you the whole video game world. I can't read those things, but kids are good at it! Not only can they read them, but they use them to plan all the different places that they're going to go. So, they're thinking several steps ahead. They're figuring out their strategy. Those same kids will tell you they can't do multi-step problems, but they just did it.

Does anybody have kids in their class that drum on the desk, either using pencils or their hands? Dante was like that. Turns out, he was keeping time in fractions. Those kids are using patterns and if you ever ask them to draw out what they're doing, it's an “aha” moment. Dante, who told me that he used to be good at math until fractions, was doing fractions and he didn't even know it.

This is part of diversifying what it looks like to do math and bringing equity to who knows math. Someone who knows math isn't just the kid who did the problem right on the board, it's also the kid who's using math in very applicable ways.

That's how we help students see they’re already mathematical. That's how we start to change the narrative that math is for them, but not for me. We change it because we show students how they're already doing it. Part of that is changing their schema: how they think about themselves and how they think about math.

Do you know what a schema is? Schemas are our neural networks—our brain’s way of organizing our thoughts and experiences. We all have them. We all make them. These are the things that lead people to have the kinds of experiences that Dante had and lead them to say that they’re not a math person.

I want you to think about how schemas help us make sense of our place in the world. If my schema, which is made up of my experiences in math, had been Kayla's experience, then that's going to teach me that I am not a math person. That I can't do it. That's a schema that I must now break.

It's not enough to tell kids they can do it. We must break their schema by showing them and giving them new experiences that help them understand that they can do math, that they already know math, and that they are already making sense of math. That's what we must do. So, how are we doing it? We're going to use an asset-based approach.

This is where we talk about what students are doing right. Identify their strengths and build on those. Look at how to unify how they feel about themselves in math and let them know that they're truly mathematical. Help them make connections in what they're doing to the math that they're learning. Use those connections to help students grow even further.

If you've never taken an asset-based approach, here's how you get started. You identify and build on your students’ strengths. What are the strengths in somebody who’s good at video games? What are the strengths in somebody who’s good at singing? What are the strengths of your student? Call them out. Give students this idea that they do have abilities, dignities, and capabilities. That will lead to a positive math identity because you're calling it out, you're naming it, you're helping students see what it is they're doing and how they can use that. Give them an anchor to grow from. That's what we need to do with all our students.

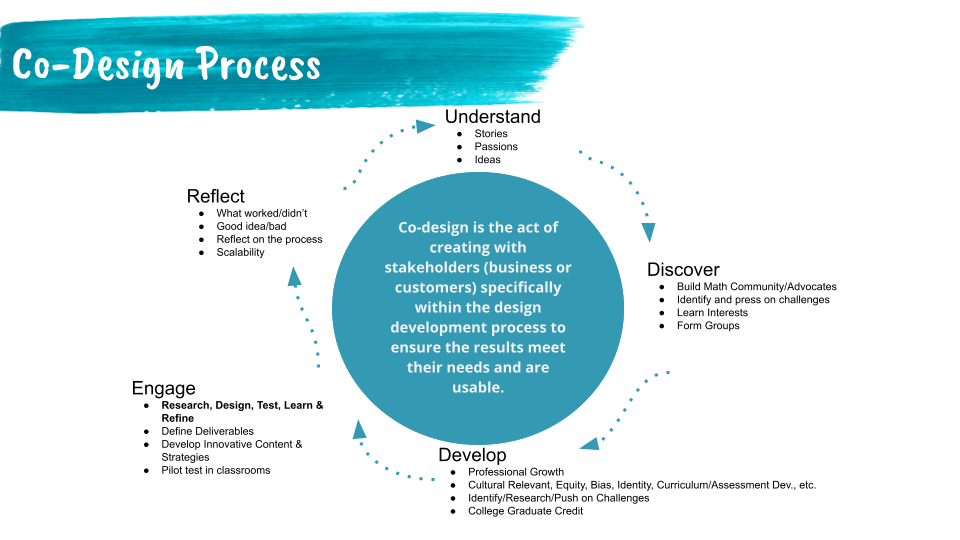

What we're doing at MIND is co-designing activities and lessons with educators, students, and families all over the country. Changing a name in a word problem is not DEI. It doesn't go far enough. It doesn't go deep enough. We had to start by understanding.

We recruited all these families, students, and educators, and we listened to their stories. We wanted to understand their passions, who they are, and what they were doing. Then, we discovered together. We formed a learning community where we talked with each other. We developed together. Things we didn't know about, we learned about together. Then, we engaged. We began to build things with these students, families, and educators, and then, we tested and learned from them.

We have classrooms of kids giving us feedback. Imagine classrooms of kids talking to designers, telling them:

That's the focus that we have in this project. At the end of the year, we’ll reflect on what worked and what didn't, and then we’ll start the cycle again. This is how we do it because we cannot do this without the stories, can we?

How can you really do DEI if you don't know people’s stories and you don't know where they're coming from? That's what you must do as you're doing DEI work in your own spaces. Get to know the stories.

Just some of the educators across the country that are designing with us.

KM: Landon is my oldest son, and he is one of the student co-designers on the Math by Design team. We have had this incredible journey alongside Twana and her team, working with brilliant, young and seasoned minds on creating opportunities to establish lessons and activities that reflect how these students want to learn.

Being a person who has math anxiety, this has created an opportunity for all of us to be transparent. In our journeys, we are navigating this process of understanding, engaging, and designing along with one another, and developing these structures for students to amplify a learning experience that is representative of who they are.

Landon loves video games, and Minecraft is one of the games that he really enjoys. Through the process of working on the Math by Design team, he got to create a cool, pixelated image that was added to one of the math lessons that help students learn about fractions. As a parent, it really made me sit back and say, “Wow! What?” At what point in his life would he ever get an opportunity to create lessons around math that his peers across the nation are going to engage with?

I love his excitement about this work. It's been great to be a learner alongside him through the parent lens. I find that too often we, as parents, don't have the tools and resources we need to effectively support our kids at home in their learning. In doing this work, I got to be a voice and advocate for parents in structuring family resources as they learn together in their math journeys.

I want to share a testimonial aside from my own. There is a group that did a feedback session with a bunch of fourth graders who had the opportunity to complete one of our math playbooks. One of the students said,

If you're going to do this [project], you should actually go for it because this is really great for us kids to learn.

This gave us a demonstration of what can happen when you allow kids to be their authentic selves in the process of co-designing their learning experience. As a parent and educator, I got to witness how this work not only impacts my son Landon, but students like him. I've been so grateful for this opportunity.

TY: I think this is a takeaway for those who want to do DEI work: the designing with students. Making your own family student group is something you could do back in your districts and classrooms. Work with students and see the effect that it has. Students are shocked that we want them to help us with this. They have so much to share, and we have learned so much from just working with them. It's amazing.

So, what have we learned from all of this and what can we do to make change happen?

One of the big things that we learned is to diversify what it means to do math, and who is a doer of math.

We must put teachers in the position to facilitate student thinking--really facilitate because kids must do the hard thinking, whether they're right or wrong. We must honor that because it's the only way we can push them. We love kids! That's why we're educators. We don't want them to struggle. We want to run to rescue, but we must hold back. We need to truly facilitate thinking and learning so that students understand that they can succeed.

The next thing we learned is the idea of positioning students.

We need to position students as authors of their own learning--how you bring equity to what it means to know math. We need to understand that students are already mathematicians. The problem is too often, we feel like kids are blank slates but they’re not! There's this thing called “funds of knowledge”: the things that you bring from your home, from your culture, from your community. We need to understand what those are. Give kids a chance to share those and then build from where they are. This is how we position students.

The third thing that we learned is we need to support kids as they're developing their soft skills.

We need to do this through inclusion--by including a variety of strategies and ways about thinking about math, helping them understand their math identities in a positive way. This is where perseverance comes in--growth mindset, communication, and giving kids opportunities. These will help them develop those soft skills and know that they have a place in society for using math in powerful ways.

In The Pedagogy of Confidence, Dr. Yvette Jackson focuses on potential. One of the things she says is,

When you have confidence about the potential of students, you help to push them to the outskirts, the limits of their mind.

Students like Dante feel like they don't have any potential. We need to use an asset-based approach to identify that potential, facilitate student thinking, position them as authors of their own learning, and then support them. We need to help them realize that they can do math and that they can go to the next level.

There is nothing that is stopping students from learning and developing the confidence they need to be successful. The confidence that they will need to have in their mathematical self to be able to go to a bank and secure a loan or negotiate a salary with a future employer.

Students need that confidence in math, and we must give it to them.

That's the work we're trying to do because in the end, when we talk to students and ask them:

We want them to say, I am.

Listen to Twana and Kayla’s full conversation on the SXSW EDU stage here and explore MIND’s position on DEI here.

Kelsey Skaggs was the Communications Manager at MIND Education. She enjoys highlighting the work of colleagues and partners who champion MIND's mission.

Comment