True or false: students will learn best when they are taught through their preferred learning style which can be auditory, visual or kinesthetic?

If you answered true, you are incorrect but far from alone. This is a widely held myth. In fact, more than 90 percent of teachers surveyed by educator Dr. Sanne Dekker and her colleagues, believed it as well.

Why is this misconception so ubiquitous? This was recently a topic of discussion among our team at MIND Research Institute because teachers sometimes ask us how our visually-based ST Math games account for different learning style preferences.

The learning styles myth is certainly appealing. After all, students differ in their background knowledge, rates of learning, and how they prefer to receive information. It seems natural then to assume that teachers can improve student learning by teaching their students in their preferred learning styles.

However, a team led by cognitive psychologist Dr. Harold Pashler reviewed decades of research and found no compelling evidence that matching instruction to preferred styles enhanced learning.

Misconceptions about learning styles are also fueled by the knowledge that different regions of the brain predominately process auditory, visual and kinesthetic information. While that is true, these areas of the brain interconnect with each other, allowing information to transfer between those different sensory regions. The brain works as an integrated whole, not discrete, closed-off compartments.

But, wait, you say. I’ve seen evidence in my own classroom that students learn better in their preferred learning style. Such observations are linked to a psychological phenomena called confirmation bias: the tendency to confirm one’s belief and neglect the counterevidence. For example, those who strongly believe that matching instruction to learning styles is important are more inclined to notice situations that seem to confirm that, and disregard or downplay instances that are at odds with the myth.

At MIND, we match our mode of instruction with the content and learning goals, not preferred learning styles. For example, we value deep, conceptual understanding of math, and that guides our design of ST Math. When developing our games, we think about the content first, and let that inform how it is taught – not students’ preferred learning style.

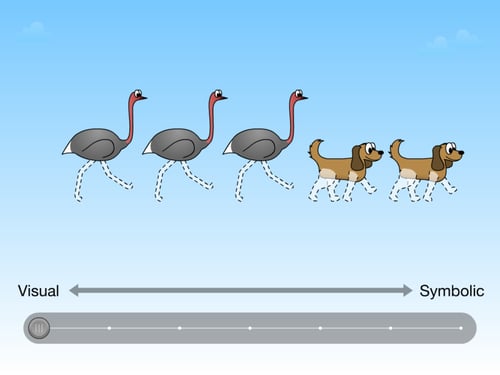

In teaching multiplication, for example, ST Math initially presents it entirely in visual form. Here, students count the numbers of legs:

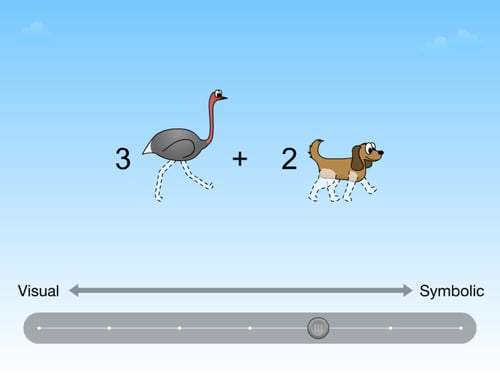

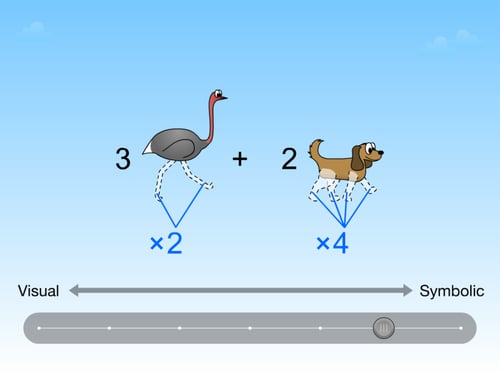

Next, students are shown a number next to each animal so that they can consider that many animals when calculating the total number of legs:

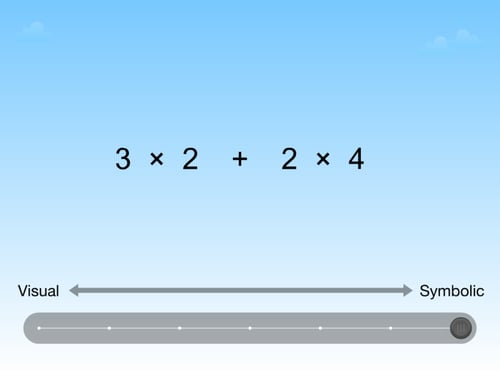

Finally, purely symbolic math is introduced:

This is just one example of how ST Math games are strategically designed to help learners effectively interpret feedback, form patterns, and develop a deep understanding by forming meaningful connections – between different math problems and also different ways of representing the same math problem.

By busting this myth, we hope to reduce teachers’ unnecessary concern about matching instruction with their students’ various learning styles, and instead re-focus on the more productive question of which way of presenting content best fits the concept being taught.

---

More information about learning styles can be found in the following articles that also formed the basis for this post:

Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105–119.

Riener, C., & Willingham, D. (2010). The myth of learning styles. Change: The magazine of higher learning, 42(5), 32–35.

Although we could not find compelling evidence to support that teaching to preferred learning styles helps students learn, are there other benefits to asking students their preferred learning style? Tell us by tweeting to @MIND_Research!

Martin Buschkuehl, Ph.D. is Education Research Director at MIND Research Institute and a Research Adjunct Professor at the School of Education, University of California, Irvine. Cathy Tran, Ph.D., was a Design Researcher at MIND Research Institute.

Comment