A few years ago, I remember teaching a classroom full of students who weren’t so excited about learning math. “It’s okay,” I said to the bored and joyless students, eager for the lesson to end. “I don’t need you guys to like math. I just need you to do it.” Now I look back and think, “What a missed opportunity….” It’s a part of my growing list of Brandon’s Brilliant Blunders.

The question at the heart of my reflection is whether enjoyment is a nice-to-have—as if learning were on par with doing the dishes, vacuuming, or raking leaves—or whether joy should be considered an essential component in any kind of education.

As it turns out, it’s the latter. Joy—true enjoyment—is critical for deeper learning. In this blog, we’ll explore how to design math experiences that help students become more engaged with their education and boost their learning experiences.

Math Anxiety: The Joy Killer

In a recent blog, we explored some causes of math anxiety and offered practical ways to conquer it with brain-based learning strategies. Here, I’ll offer some more tangible solutions to boost mathematical joy.

The truth is, we’ve seen a slew of articles that highlight the concerns of math anxiety, but we don’t hear enough about how we can tackle math anxiety that would prevent its ugly head from resurfacing in classrooms. To find solutions, we need to dive into anxiety a bit differently, because the more anxious we are, the less likely we are to learn. (Students with high levels of anxiety are likely to underperform academically by an entire school year).

Why is that exactly, and what can we do about it?

Rethinking Motivation

Anxiety isn’t detrimental simply because it’s an emotion we don’t like to experience. It’s harmful because it’s pacifying, and it hinders learning. When we’re anxious about something, we generally try to avoid the object of our anxiety—or the situation that induces feelings of anxiety.

Anxiety also releases cortisol, sometimes called the “stress hormone.” While cortisol is normal—and ebbs and flows for all of us—it blocks noncritical fight or flight behaviors. The hippocampus, for example, is a key player in our brain’s ability to learn and can become impaired due to high cortisol levels. Chronic levels of cortisol can even damage the hippocampus over the long run, which makes it even more difficult to learn.

This is the double-edged sword of anxiety. Key learning centers of our brain are less effective during the little engagement with math we’d even allow while anxious—which gives us a lens with which to pick up on any cues about someone’s anxiety. If they are avoiding math (or they need to be coaxed into engaging), that’s an indicator of anxiety. If they go about as deep as a rock skipping off the surface, that’s another indicator.

Here’s an example that will sound familiar:

I attended a family math night some years back that centered around the passport-raffle model. The prize on the stage? A really cool bike. I bet you can predict what happened.

Families would walk up to a station and immediately ask for a stamp on their passport. This is what skipping off the surface looks like. They’re willing to “touch” math for only a second and leave. More than a second of involvement and you’ll be doing all kinds of mental gymnastics to coax them into deeper engagement.

This was so common that there was a full-time raffle guard that would stop kids and parents from submitting for the raffle until they’d visited all ten stations (enter dismay and a forehead bonk).

The smiles weren’t about math.

The Problem with External Motivation: Joy Can’t Be Forced

Here’s the thing with external motivators: they have “…detrimental effects on the performance of any task that requires creativity, conceptual understanding, or flexible thinking” (Edward Deci, Why We Do What We Do).

We’ve all been guilty of putting these external motivators on a pedestal. Whether it’s doing math just to get a good grade, a star next to our name, or to win a prize, we’re often swayed by motivators outside of the joy within the task itself. External motivators lead to shortcuts and short-term thinking that cause long-term damage. We can’t force joy.

Step 1 in moving towards joy? Leave external motivators behind. If the task flops without those motivators, that’s okay. We can now focus on what we replace it with: intrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic Motivation: We Can All Be “Math People”

Intrinsic motivation is “…the drive to do something because it is interesting, challenging, and absorbing” (Daniel Pink, Drive). This is the emotional state essential for high levels of creativity. Intrinsic motivation is something inherent within all of us.

Recess is a great example of kids’ inherent and intrinsic motivation. They will put forth incredible effort for prolonged periods, even if they don’t have to. “Just 5 more minutes” is the anthem of all children engaged in play—it’s also generally considered one of the more powerful ways to learn (The Anxious Generation).

One component of play is that it’s effortful. Kids are huffing and puffing after recess, playing the video game even while rubbing their tired eyes, and snapping the next Lego in place with sore fingers. Give kids time to create their own play, and they’ll find a way to make the experience harder, like shooting hoops with their eyes closed or seeing who can hold their breath the longest. This is because we feel powerful when we overcome playful challenges.

Math should take a page out of the playbook of recess. The trick is that we shouldn’t try to dress up the same old math experience with external motivators. Kids see right through that. We need to be willing to improve the core math experience itself. That starts with playful challenges.

When it comes to play, tasks that lead to mistakes are the point. And as adults, we are so afraid of mistakes that we rob ourselves of joy. The good news is that passivity and helplessness are not our natural human state. Humans are primed for intrinsic motivation. And on the other side of struggle? Joy.

…best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult.

– Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

Bring Joy to Life

To bring joy to life in a student’s math journey, we need to embrace two key principles:

- Ditch the External Motivators: Forget the passport raffle model or the $5 for every A on the report card. You’ll know a highly external environment when you see it.

- Playful Struggle: Struggling in math should feel like a playful challenge, not a tedious task. By crafting math experiences that are light-hearted and engaging, students can find joy in the struggle.

Playful Struggle: The Game-Changer

Mathematical joy does not happen when we’re simply “entertained” and passive; it happens when we push ourselves really far, working hard to accomplish something difficult. Sometimes this feels naturally playful, but often it doesn’t.

Math is generally more playful when:

- We are in a risk-prone environment in which mistakes aren’t heavy. Having to up our game is exciting because it means we are strong and capable.

- We have full control over how we tackle the challenge—play isn’t a chore.

- We have a sense of urgency that comes from within—it’s exciting, not forced.

- We feel that success is within reach.

All in all, we know we’re being playful in the struggle when we feel powerful through struggle. We feel like we want to get to the bottom of it right away and, at the same time, are curious to give the unproven route a shot because we openly embrace risk.

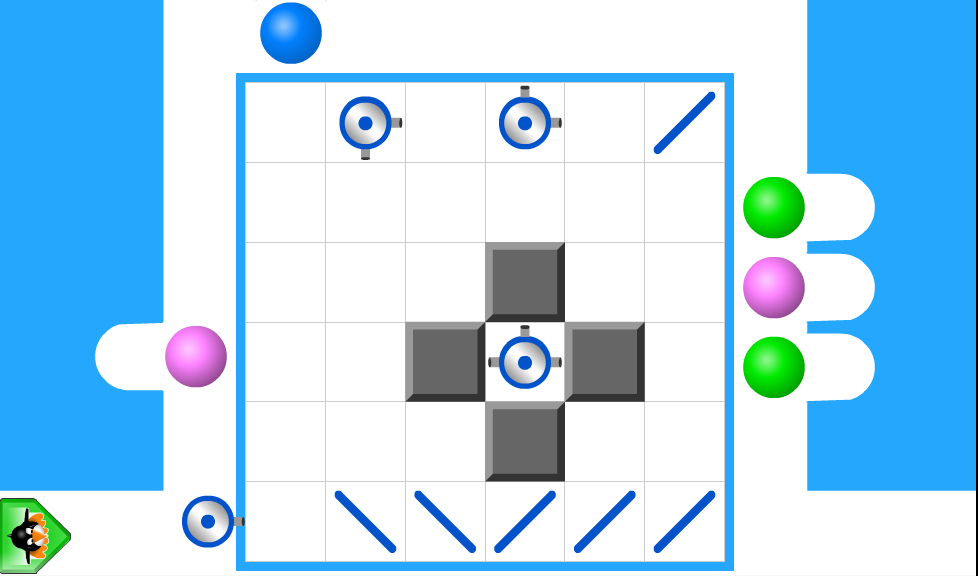

Take one of our MathMINDs games, Turtle Sums. Inspired by an ancient Chinese tale, Turtle Sums introduces you to Lo Shu, a magical turtle with a unique pattern on her shell. Paired with one of our captivating MathMINDs storybooks, the object of the game is to decipher the secret code on Lo Shu’s shell, and on each of her family members. You know you’ve unlocked each shell when the turtle is happy and smiles. Numbers out of place make turtle shells itch—and the characters will let you know when that happens as well.

Games like this aren’t enjoyable because of its graphics or because “we don’t know we’re doing math.” They’re enjoyable because they level up the effort on similar puzzles and don’t start by telling you exactly what to do. Exploration, not right answers, is the driving force. When we teach math as a one-and-done to get the right answers immediately, we’ll feel pressured to dress math up again.

Transforming the way we teach and perceive math can unlock a profound sense of joy in students. It’s not about dressing up the math; it’s about changing the essence of the mathematical experience itself. When we do, we’ll sense a shift from us trying to “make math fun” to students creating their own joy.

That’s when we’ve found the sweet spot.

Looking for a new approach to math education that fosters inclusive and engaging learning environments? Discover how MIND’s revolutionary approach to math learning can prepare your students for the challenges of tomorrow.